QUESTION – I know what the POH says, but is 2400 feet really enough runway for a Malibu, Mirage or Meridian?

ANSWER – I’m Glad You Asked!

The short answer to this question is yes, in many cases, but how can we know for sure? Clearly this is a density altitude related discussion and the full and complete answer lies in the performance section of your POH, so look there first.

Now, some of you may say, “I checked the POH and it says that the aircraft can do it, but I don’t trust this data since the aircraft is not new and I am not a test pilot”. So how can we be sure?

According to The Airman’s Information Manual (AIM), it is possible to judge your aircraft’s current performance by using the ½ runway rule. Now, this rule is provided for unimproved runways; however, we can apply it to improved runways as well. The ½ runway rule is stated in AIM 7-5-7 as follows:

When installed, runway half-way signs provide the pilot with a reference point to judge takeoff acceleration trends. Assuming that the runway length is appropriate for takeoff (considering runway condition and slope, elevation, aircraft weight, wind, and temperature), typical takeoff acceleration should allow the airplane to reach 70 percent of lift-off airspeed by the midpoint of the runway. The “rule of thumb” is that should airplane acceleration not allow the airspeed to reach this value by the midpoint, the takeoff should be aborted, as it may not be possible to liftoff in the remaining runway. Several points are important when considering using this “rule of thumb”:

a. Airspeed indicators in small airplanes are not required to be evaluated at speeds below stalling, and may not be usable at 70 percent of liftoff airspeed.

b. This “rule of thumb” is based on a uniform surface condition. Puddles, soft spots, areas of tall and/or wet grass, loose gravel, etc., may impede acceleration or even cause deceleration. Even if the airplane achieves 70 percent of liftoff airspeed by the midpoint, the condition of the remainder of the runway may not allow further acceleration. The entire length of the runway should be inspected prior to takeoff to ensure a usable surface.

c. This “rule of thumb” applies only to runway required for actual liftoff. In the event that obstacles affect the takeoff climb path, appropriate distance must be available after liftoff to accelerate to best angle of climb speed and to clear the obstacles. This will, in effect, require the airplane to accelerate to a higher speed by midpoint, particularly if the obstacles are close to the end of the runway. In addition, this technique does not take into account the effects of upslope or tailwinds on takeoff performance. These factors will also require greater acceleration than normal and, under some circumstances, prevent takeoff entirely.

d. Use of this “rule of thumb” does not alleviate the pilot’s responsibility to comply with applicable Federal Aviation Regulations, the limitations and performance data provided in the FAA approved Airplane Flight Manual (AFM), or, in the absence of an FAA approved AFM, other data provided by the aircraft manufacturer.

In addition to their use during takeoff, runway half-way signs offer the pilot increased awareness of his or her position along the runway during landing operations.

It is important that you know the midpoint of the runway. I get this information sometimes from the airport diagram by noting the position of intersecting taxiways. If there is no obvious way to get the midpoint, I taxi the full length of the runway counting the centerline stripes. I then taxi back downwind counting half of the stripes and note a landmark at the midpoint.

I complete a thorough run-up and a runway environment flow. I use 20 degrees of flaps instead of 10 degrees. I then taxi into position, hold the toe brakes, and set full power. I use the same “callouts” on the short field takeoff roll as I do on a runway of normal length and they are as follows:

- Airspeed alive

- Gauges green

- Annunciator clear

- 60 knots – crosscheck (this callout should occur at or prior to the ½ way point; typically before the 1000 foot mark)

- 80 knots – rotate and pitch for 12 degrees nose up (Vx) (visually this is one dot above the 10 degree bar on the attitude indicator)

- Positive rate and clear of obstacles – lower the nose to 8 degrees nose up (Vy)

- Flaps up to 10 degrees

- Gear up

- Passing 100 knots – Flaps up (do not look away from the attitude indicator for more than a quick glance to ensure the pitch attitude remains positive and correct.

- Trim for the deviation (flight director) bars

- Autopilot on

- Verify “D bars in the blue” and that the aircraft is performing as commanded.

I suggest that you practice this procedure before applying it to an actual short field departure and here is how you can do just that:

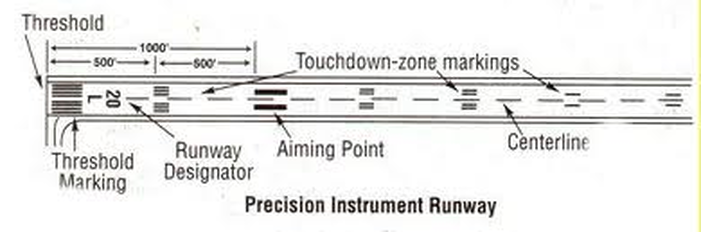

The next time you are departing from a runway with precision approach markings, take a close look at the runway distance markers. These markers are 500 feet apart. This means that the second set of markers (officially known as the aiming point, and affectionately known as the captain’s bars) is 1000 feet from the threshold.

Let’s say you want to know if you can depart from a 2000 foot runway. You can simulate taking off on a 2000 foot unobstructed runway by using the distance markers on any runway which is so equipped. According the ½ way rule, your Malibu, Mirage or Meridian aircraft should be at 60 knots (70% of your rotate speed) before reaching the captain’s bars on the takeoff roll. If the aircraft is not at 60 knots by this ½ way point, you should use the remaining 1000 feet to abort the takeoff.

Since many things can affect the performance of your aircraft, the ½ way rule may not work effectively if runway conditions are inconsistent, such as with snow and slush.

If you are concerned about landing performance, remember: Your Meridian aircraft is capable of landing on any surface from which it can safely takeoff, given the same conditions and proper technique.

I recommend that you consider noting the position of the aircraft at 60 knots on every takeoff. It will help you spot any deficiency which adversely affects aircraft performance and give you the confidence to safely operate your aircraft under a greater variety of conditions.

Fly Safely – Train Often

“I’m Glad You Asked” is a regular column written by Master Flight Instructor Dick Rochfort. Dick answers questions which come up frequently while conducting training in the Malibu, Mirage and Meridian aircraft. If you have a question for Dick, you can send it to him at mail@rwrpilottraining.com. He’ll be … “glad you asked”.